This guest post is written by the poet, writer, teacher, Timothy Dyke:

One of the many things I love about da Shop is being able to chat about books with whomever may be in the store when I'm browsing. We can't do that in person right now, but fortunately da Shop has found a way to continue our conversations around books. What follows is a rumination, more than a review. I was asked what I think of a Joy Harjo collection, and what follows is my response. I offer it in a spirit of conversation and reflection.

Put down that bag of potato chips, that white bread, that bottle of pop.

I read that line in my fifth week of quarantine. It’s May 4th, and I’ve hardly left my Makiki apartment since March 13. “Yeah,” I think to myself when I encounter that first line in the first poem in this book by Joy Harjo. “I should definitely eat more leafy greens.”

Turn off that cellphone, computer, and remote control.

I can’t disagree with this advice either. I’m holding the book in my hands. I reflexively look at the cover. “Could she be writing this to me?” I ask myself. “Is this advice for these times we’re living in right now?” I check the copyright date. This book came out five years ago.

Open the door, then close it behind you.

Take a breath offered by friendly winds. They travel the earth gathering essences of plants to clean.

Give it back with gratitude.

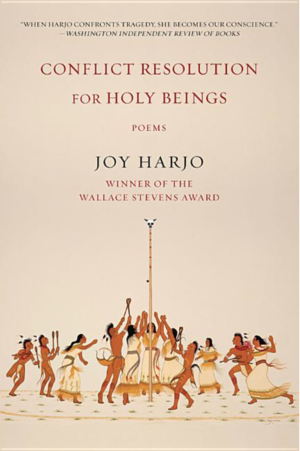

The words in italics above are from “For Calling the Spirit Back from Wandering the Earth in Its Human Feet,” the first poem in the 2015 collection Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings by Joy Harjo. I’m about to write a review, of sorts, but first I want to narrate a quick little anecdote. Think of this as some kind of disclaimer. I haven’t thought of this memory for at least a decade, so I can’t swear that I’ll get every detail right. I’m aiming for, as Tim O’Brien might say, “story truth” over “happening truth.”

During the early 2000s, I wrote a few articles for the now-defunct Honolulu Weekly and the now-merged Honolulu Advertiser. Mostly I wrote art and music reviews. I can’t say I was great at it. I didn’t exactly know what I was doing. For better and for worse, I figured things out as I went along. One assignment put me in the galleries of The ARTS at Mark’s Garage on a weekend afternoon during Girlfest, an art and literary celebration centering on the stories of women. My editor had asked me to review the show on the gallery walls. I can’t remember the specific theme of the exhibition, but all the art was by women. I walked through the large front room, staring at photographs, writing in my notebook.

Eventually I noticed a gathering of people in a back room. They seemed to have stopped talking as I passed by. I wondered if it mattered that I was the only man in the building. I wondered if it mattered that I was reviewing these artworks for the city paper, when I didn’t really seem to be part of the intended Girlfest audience. As I was looking at a drawing I admired, I became aware of a woman standing nearby. She introduced herself as the artist of the piece. When I introduced myself as the reviewer of the show, she said nothing. Feeling compelled to explain myself, I told her that a woman had been assigned to review this show by women, but that she had come down with a cold. I was a last-minute replacement. I eventually wrote a positive review of this exhibit at ARTS at Marks. I led with the anecdote about talking to the artist. I led with questions about my suitability as a reviewer, given that I was not part of the intended audience.

Perhaps that was a long-winded digression, but I’m thinking of that story right now. In Conflict Resolutions for Holy Beings, Joy Harjo writes from her specific experience as a woman of the Mvskoke/Creek Nation. She writes from her experience as a jazz musician. She writes from her experience as a woman who walked out of a hotel just off Times Square at dawn on the fourth morning since the birth of her fourth granddaughter. She writes from her experience as an indigenous person who feels a connection to Hawai‘i. I read these poems as I might listen in on someone else’s conversation, and yet these conversations speak to me too. When I encounter art – especially when I encounter art that I perceive to be inspired by cultures different from my own -- I regard questions of intended audience because I don’t want to assume that I know exactly what I am looking at. I think I’m entitled to my own reaction, of course, but I don’t want to assume my reaction is universal. I don’t want to fuse my experience onto the experience of the art-maker. I think about this white guy from Pennsylvania I knew who moved to Waikiki for three months, and then returned home to Scranton with a tattoo of Queen Lili’uokalani on his bicep. I don’t want to be that guy. I don’t want to colonize anyone else’s vision. I don’t want to be so presumptuous as to assert that Joy Harjo was writing these poems directly to me.

There are times, though, when I almost can’t help myself. Check out these lines from part four of the long and central title poem:

We are here dancing, they said. There was no there.

There was no “I” or “you.”

There was us; there was “we.”

There we were as if we were the music.

You cannot legislate music to lockstep nor can you legislate the spirit of the music to stop at political boundaries—

--Or poetry, or art, or anything that is of value or matters in this world, and the next worlds.

This is about getting to know each other.

This book is about getting to know each other. The words affect the reader as the jazz sounds of Harjo’s sax heroes affect those who listen to the music. The tone is specific and personal, and through that specificity, universal truths emerge. I’m not sure it’s my place to tell you what truths she is sharing. I’m not sure my interpretation is as important as my enthusiasm. I am excited to tell others to read Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings because we are isolated in our homes right now and this book finds a way to bring all who encounter it together. As I type this paragraph, there is a guy with a noisy weedwhacker working on a hedge right outside my window. The noise prompts me to think of one last anecdote. In 2012, Joy Harjo gave a reading on a Saturday afternoon at the Kamakakuokalani Center for Hawaiian Studies on the University of Hawaii Manoa campus. The room was crowded and hushed as the poet read from her most recent work.

A loud noise sounded. Some kind of fire alarm had been accidentally triggered. Harjo stopped reading, of course, and we all waited for the noise to stop. The noise didn’t stop. One of the hosts of the reading ran off to see what she could do. Some people covered their ears. Some people disappeared into their phones. After five minutes of unceasing noise, Joy Harjo walked to a chair in the front row and unbuckled her saxophone case. She pulled out her instrument and started playing. It’s hard to explain how someone can accompany a fire alarm, but the sound in the room transformed from disturbing to inviting, from industrial to personal. Eventually the alarm stopped. She played for a little bit longer, and then she read from her book some more. Joy Harjo has the power to make sense out of cacophony. This is why I think everyone should read Conflict Resolution for Holy Beings. She finds love in the noise. She writes poems you can dance to. She asks us to remember the source of the gift.

And when you dream, remember the source of the gift of all dreaming.

And when your heart is broken, remember the source of the gift of all breaking.

And when your heart is put back together, remember the source of all putting back together.

This book can become a source for putting back together. I recommend it as a healing read during these times of uncertainty and crisis.

Timothy Dyke is a writer and teacher who lives with parrots in Makiki. He is the author of the chapbook, Awkward Hugger, and the prose poem collection, Atoms of Muses, both published by Tinfish Press. Tinfish published his new book, MAGA, in January, 2019. In 2012, he earned an MFA in Creative Writing from the University of Arizona. Since 1992, Timothy has taught English to high school students at Punahou School.